Post by Sierra Woodruff

Sierra Woodruff is a Ph.D. candidate at the University North Carolina at Chapel Hill in the Curriculum for the Environment and Ecology.

As a graduate student, there is a lot of uncertainty in my life: When will I finish my degree? Will I get a job? Where will it be?

We all confront uncertainty when we plan for the future. Our local governments are no different. They may ask: how will our population grow? What will be our future demand for water?

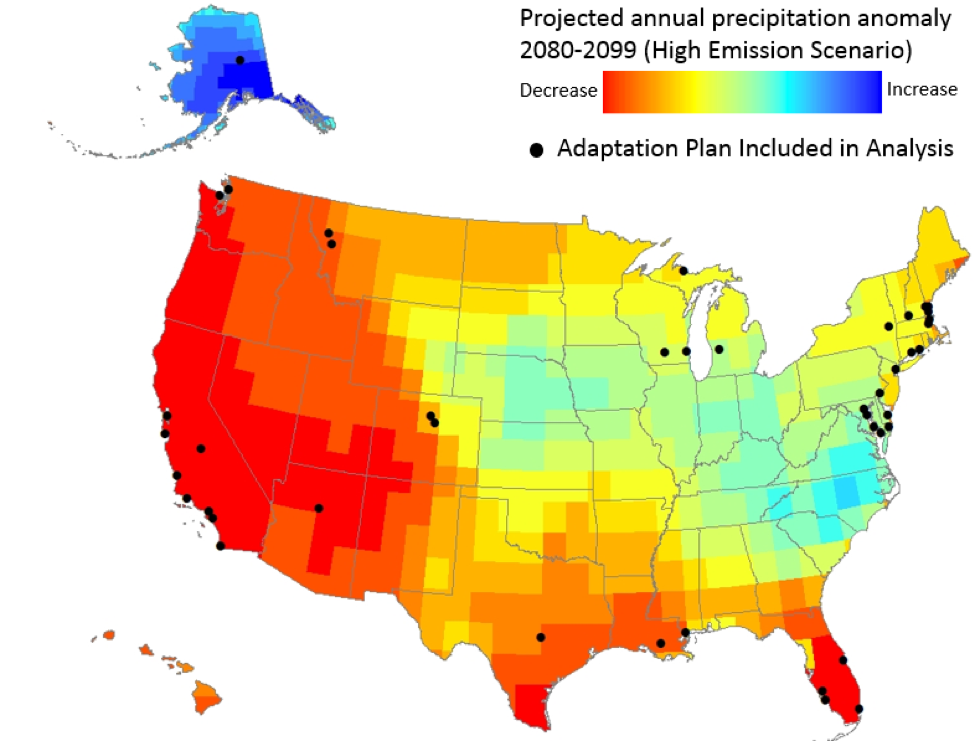

Today, local governments are also beginning to ask questions about climate change: How much will rainfall patterns change? When will the next drought be? How will it affect our drinking water supply?

The uncertainty in the magnitude and timing of climate change impacts complicates decisions our local governments make about how we should manage our natural resources, where development should occur, and how we should design our physical infrastructure.

Researchers have developed multiple approaches to help local governments to discover, assess, and address uncertainty in climate change impacts. These approaches typically emphasize the need to consider multiple scenarios of the future, select strategies that provide benefits across a number of scenarios, and establish processes for learning and incorporating new information.

But do local governments actually use these approaches? For my dissertation, I aimed to answer this question by analyzing local climate change adaptation plans across the U.S. I found that while most plans recognize uncertainty as a challenge, very few use approaches that have been recommended by researchers to address that uncertainty.

To better understand how local governments are addressing uncertainty in climate change, I then conducted informant interviews in three communities: Boulder, CO; Denver, CO and Salem, MA.

Interviewees described multiple challenges that inhibited them from using existing tools to address uncertainty. For example, it can be difficult to change deeply embedded practices of planning for a single, best-estimate of the future.

Interviewees also discussed multiple ways they are considering uncertainty. Most importantly, local governments are beginning to change the conversation about climate change to focus on their sensitivities. In other words, they are exploring how the things most valuable to their communities – drinking water, clean air, thriving economy, and recreation – may be affected by climate change.

Focusing on “what will happen?” may reinforce the practice of planning for one estimate of the future. By emphasizing how they are sensitive to the impacts of climate change, local governments are beginning to ask a new and more helpful question: “Given that one cannot predict the future, what actions that we can take today will serve us best in the future?”

This requires scientists to change how they provide information. Rather than assume that all local governments need is information about how climate may change, scientists need to engage with decision-makers and tailor information to decision-making context.

This approach may serve us all well as we plan for unknowable and uncertain futures. Before asking what might happen, we should first consider what is most valuable to us and what is necessary to maintain it long into the future.

The full results of the study can be found in the journal Climatic Change.