Post by Jordan Kern

Jordan Kern is a Research Assistant Professor at the UNC Institute for the Environment. You can learn more about his research and teaching portfolio at http://jdkern.web.unc.edu/.

Jordan Kern is a Research Assistant Professor at the UNC Institute for the Environment. You can learn more about his research and teaching portfolio at http://jdkern.web.unc.edu/.

Eliminating greenhouse gas emissions in the electric power industry might require it to change from top to bottom – the technologies that are used, the business models employed, the number and scope of market participants, and the regulatory oversight required. The only thing that we can safely say won’t change are the laws of physics that impose constraints on the operation of power systems.

The good news (at least for folks who are concerned about climate change) is that the electric power industry is changing quickly, largely due to technological advances and policy pressure. What that means for conventional, vertically integrated electric power utilities – companies like Duke Energy— is a little uncertain, but they’re spending a lot of time thinking about how they can be successful players in the grid of the future.

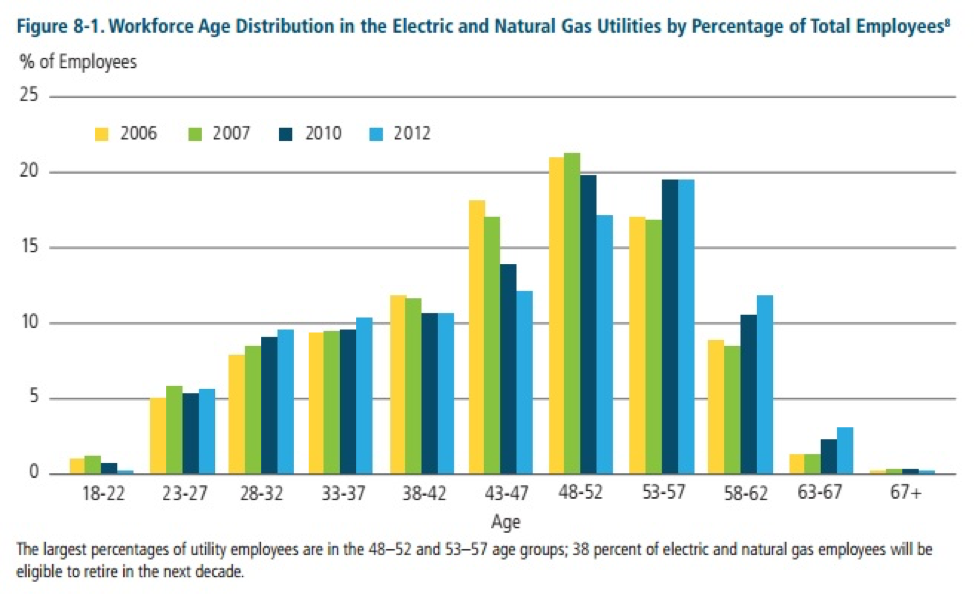

As the electric power industry evolves, another thing we’re learning is that there is a big need for an influx of new workers with a broader set of expertise. Some of this need is related to the facts of life: baby boomers who worked their whole careers at power companies are retiring. Some industry estimates project that 50% of the workforce at electric power utilities will retire over the next several years, and these folks will need to be replaced.

Image from Utility Dive

But perhaps more importantly, the types of skills needed in the electric power industry are changing in a number of ways:

- For one, the future of the industry may not be dominated by conventional electric utilities or for that matter, even by suppliers of energy.

- In a grid dominated by renewables, demand side management (i.e., managing and reacting to customers’ behavior) and storage will become critical components.

- Even at big utilities, the pathway to a job is no longer limited to mechanical and electrical engineering. Increasingly, utilities need workers with skills in data science, software development, business, and marketing.

In a lot of ways, this shift benefits UNC students. Even though the technical rigor necessary for a career in the energy industry has been available at UNC for a long time, without a significant undergraduate engineering presence on campus, some doors have been closed to our graduates.

The shifting nature of energy industry means new doors are springing open. We just need to make sure UNC grads are walking through them.

Part of that means exposing students to the benefits of marrying their intellectual and philosophical interest in sustainability to tangible career pathways. For more on the incredible strides UNC has taken in this regard, you should read UNC professor Greg Gangi’s recent blog post.

Another important aspect of preparing students for new opportunities in the energy industry is adapting undergraduate curriculums. At UNC, the Curriculum for the Environment and Ecology (ENEC) is doing just that, having recently hired a new lecturer in Energy.

I’ve tried to do my own small part too, by developing an Energy Modeling and Analytics course (ENEC 490), which is offered in the fall. The course uses a “flipped classroom” approach, with formal lectures delivered online via YouTube, and in-class time used to develop coding and modeling skills through the completion of industry case studies.

One of the things I’ve been most impressed with over the last several years is how these shifts in focus at UNC and within ENEC have been spurred by student interest.

On the part of the university and ENEC, this shows not only a willingness to adapt quickly (not always a strength of big institutions), but also a recognition that, in terms of defining societal priorities and creating new areas of economic and intellectual growth in the future, the students are often the teachers.