By Arbor Quist

Arbor Quist is a Ph.D. candidate in the Epidemiology Department at UNC-Chapel Hill Gillings School of Global Public Health

The Importance of Private Wells in North Carolina

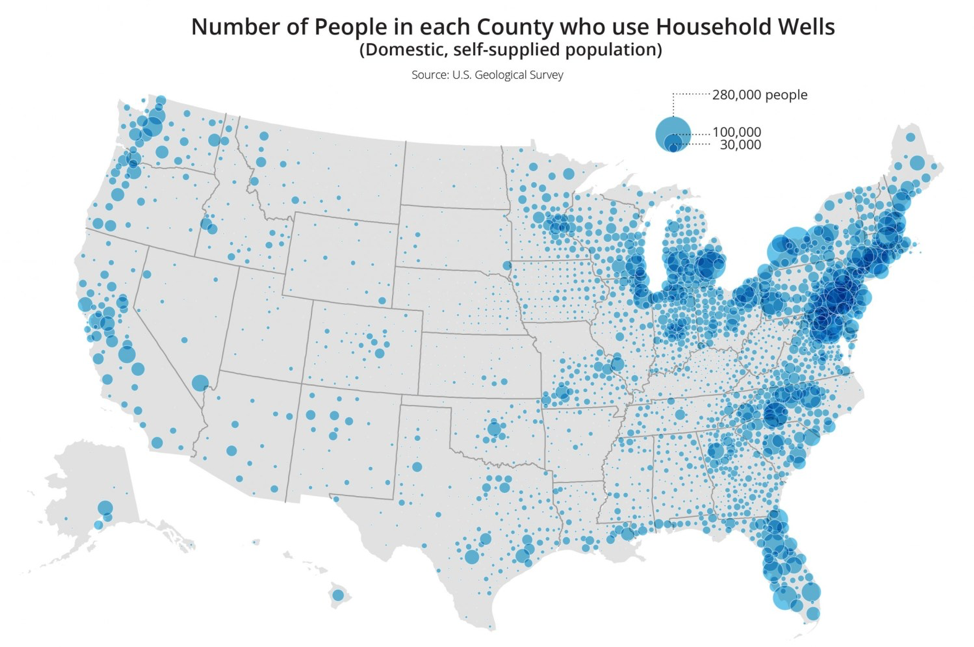

About 3.3 million North Carolina residents—almost a third of its population—rely on household wells or other small residential water systems. Private well water is not regulated under the Safe Drinking Water Act and wells stand at higher risk of contamination than community water supplies—especially near industrial areas with toxic chemicals or large amounts of manure. Flooding from heavy rain and hurricanes can spread biological and chemical contaminants from their sources, causing surface and well water contamination.

Well test data for North Carolina private wells show that few well owners regularly test their water. Because of the large number of North Carolinians on well water, recent water contamination caused by some industries, and the frequency of recent heavy hurricanes, many researchers, communities, and non-profit groups are working on testing and improving North Carolina’s well water quality.

Formation of the NC Well Water Round Table Working Group

A new North Carolina Well Water Working Group recently formed to bring together well water advocates from various areas—from law and public health research to planning and community advocacy. This group seeks to foster communication and collaboration between groups and disciplines, as improving well water in North Carolina requires excellent coordination and appropriate pressure on local, state, and industry leaders.

The group grew out of conversations between Maria Savasta-Kennedy (UNC School of Law Professor), Mike Fliss (Research scientist with NC Injury Prevention Research Center and NC Division of Public Health), and myself (Arbor Quist, epidemiology PhD candidate) of how to better connect scientists, lawyers, policy-makers, and communities to make lasting improvements on well water quality in North Carolina. While other, occasional well water meetings have been extremely productive, this new group plans to meet quarterly to continue conversations and encourage partnerships.

The first NC Well Water Round Table was hosted by the UNC School of Law School on January 10, 2020, with over 40 participants. The majority of the meeting consisted of thorough introductions, with participants discussing their NC well water work and the challenges they have encountered. This ranged from attorneys representing people with contaminated wells who seem to have little legal recourse to researchers’ frustration with the lack of government transparency regarding contamination and unwillingness to share data.

Community leaders talked about how research and policies often do not meet community needs, as researchers sometimes report well water results back to participants and communities without providing low-cost solutions or using the results to fight for needed systematic changes. Additionally, it can sometimes be difficult for researchers to meaningful interpret well water test results to communities, as some contaminants do not have established standards.

One theme of the round table discussion focused on the importance of avoiding parachute research, or research that parachutes into a community, collects data, publishes papers, and parachutes out without actually helping the community. While researchers may intend to work effectively with community to communicate well water results, pressures from academia often quench good intentions, as researchers are primarily rewarded for academic publications, which often do little for communities.

I hope that this multidisciplinary group will hold us responsible to our duty to residents, encourage bi-directional, community-based research focused on community needs, and urge us to link our projects, skills, and resources together to fight for clean water for all North Carolinians.

After introductions, participants from the UNC School of Law provided a summary of North Carolina’s legal requirements for testing private well water. For new wells built since July 1, 2008, the North Carolina Private Well Testing Program requires local health departments to test well water for bacterial indicators, arsenic, nitrates, nitrites, selenium, pH, and 12 metals. However, there is no regulation that well water must be tested during real estate transactions in North Carolina. The broker must disclose information about known well water contamination, above certain thresholds. Some worry that this discourages people from getting their well water tested, for fear it will lower the price of their home.

One Example of Private Well and Public Health Research at Carolina

I became involved in well water research through my adviser, Dr. Larry Engel, who is leading a pilot project in Robeson County of paired well water and urine samples. Funded by the UNC Center for Environmental Health and Susceptibility and partnered with American Indian Mothers, we are working with several collaborators in the environmental sciences and engineering department to test for metals, microbes, perfluoroalkyl substances, and over a thousand chemicals (including pesticides, antibiotics, and veterinary drugs), using targeted and untargeted analyses.

Well water can be contaminated with many different compounds and can cause various health issues, but microbial contamination is not uncommon and can result in gastrointestinal illness. While my dissertation research does not assess well water, I’m looking at how gastrointestinal illness emergency department visits patterns change over time, especially in relation to hurricane flooding and in areas near industrial hog operations. These issues may be more problematic for people on wells.

As researchers continue to examine how industry and disasters affect health and the environment, I hope that we reach across disciplines to connect with policy-makers, lawyers, government leaders, and communities to develop meaningful solutions and fight against environmental and climate injustice. I am hopeful that the NC Well Water Working Group will help facilitate this.

For more information about the NC Well Water Working Group visit: https://ncwellwater.web.unc.edu/