Post by Greg Characklis

Greg Characklis is a professor in the Department of Environmental Sciences and Engineering at UNC-Chapel Hill and Director of IE’s Center for Watershed Science and Management.

I had the opportunity to spend part of this summer living in Bozeman, Montana where I am collaborating with colleagues at Montana State University. Montana is a beautiful state and is well known for its abundance of wildlife and unique natural settings, such as Yellowstone National Park.

What is not so well known is that Montana faces significant water scarcity issues. A 2014 report from the U.S. General Accountability Office identified Montana as the state most likely to have a statewide water shortage in the next decade. Other western states, most notably California, are also facing similar water resource challenges.

Here in North Carolina current conditions this summer described by the U.S. Drought Monitor suggest that most of the state is in good shape in terms of water supply. However, fortunes can change quickly, as North Carolina learned during the droughts of 2002 and 2007-09 droughts, both of which caused serious harm to the state’s natural resources and to water dependent industries such as agribusiness and real estate development.

North Carolina’s population and water demand have been, and will continue to, increase in coming years, even as new supplies continue to become more difficult and expensive to develop. The combination will make periods of water scarcity more common, and it’s possible that climate change will exacerbate this problem. Either way, it’s clear that North Carolina is in the midst of transitioning to a future in which an abundant water supply can no longer be taken for granted.

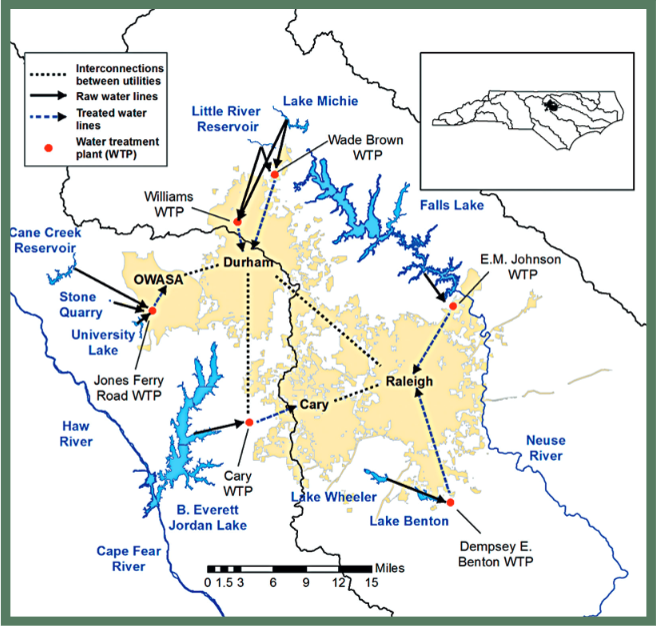

In an effort to prepare the region for this transition, I am working with a team of researchers here at Carolina and with other partners to identify engineering and economic strategies that will allow North Carolina to sustainably meet its future water demands. These strategies could include new reservoirs and more interconnections, as well as innovative economic and financial tools.

One of the unique aspects of the research project is the integral involvement of local water agencies. We are working with a number of water utilities and local governments here in the Triangle to evaluate how regulatory systems and infrastructure decisions will have to adapt as North Carolina transitions to its new reality.

As the project moves into its third year a couple of key action items the research team is addressing include:

- Understanding the impacts of population growth and development patterns (i.e. land use) on both water demands and water supply

- Developing adaptive water management strategies that balance high reliability, cost and environmental considerations, yet still capable of adapting in the face of uncertainty.

The research remains a work in progress but we are confident this collaboration will enhance North Carolina’s capacity to manage future water shortages.