By Kate Fialko

Kate Fialko is an undergraduate student at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, where she is pursuing a degree in Environmental Science with a minor in Information Science. Kate works with the Environmental Finance Center at UNC (EFC) as a LEAF fellow, interning at a host site this past summer. Previously, she worked for the EFC as a Student Data Analyst, focusing on the water rates surveys and dashboard projects.

Highlights

- Conservation-oriented system development fees more closely align water use and cost of capacity, allowing developers to pay lower fees if they build more efficiently.

- Interning though the Leaders in Environment and Finance (LEAF) fellowship program this summer allowed me to apply knowledge gained from my classes at UNC to work on a real-world problem in my community.

This summer, I had the opportunity to intern at Orange Water and Sewer Authority(OWASA) through the Environmental Finance Center at UNC’s Leaders in Environment and Finance (LEAF) fellowship program. The LEAF program placed six UNC undergraduate and graduate students at host sites in the Triangle to work on environmental finance-related projects. This fall, we will work at the Environmental Finance Centeron research projects related to our summer internships.

For one of my projects this summer, I researched possibilities for a conservation-oriented system development fee(SDF) for OWASA’s non-residential and multi-family master-metered (MFMM) customers. OWASA charges system development fees when a developer wants to connect new development to water service or increase meter sizes for existing development. These fees allow the utility to recover the cost of capacity needed to meet increased water demands.

OWASA currently charges non-residential and MFMM SDFs based on meter size, which is determined from expected peak flows. This approach is easy to administer, but it typically does not allow developers to see fee reductions if they build more water-efficient developments. For example, a two-inch meter accommodates a flow of 160 gallons per minute (gpm) while a three-inch meter has a capacity of 300 gpm. Engineers for an office building might design efficiency measures to reduce peak flow from 250 gpm to 175 gpm, but the developer would still have to pay for the infrastructure associated with full use of the 300 gpm-rated meter. Conservation-oriented SDFs more closely align water use and cost of capacity, allowing developers to pay lower fees if they build more efficiently.

To determine how OWASA might form a new conservation-oriented SDF, I first learned how SDFs are calculated and referenced case studies of other utilities’ conservation-oriented SDFs. Such fee structures are most common in the western United States, but at least two utilities in North Carolina charge SDFs based on water use, which is a type of conservation-oriented SDF.

I later interviewed local developers to get feedback on how they currently think about SDFs and what they would want to see in a conservation-oriented SDF design. Findings from these interviews allowed me to determine fee options that might be a good fit for OWASA and drew my attention to benefits and challenges of the fee structures that I had not previously considered. I also checked in with OWASA’s rate consultant to ensure that the proposed ideas followed North Carolina’s cost-of-service requirements.

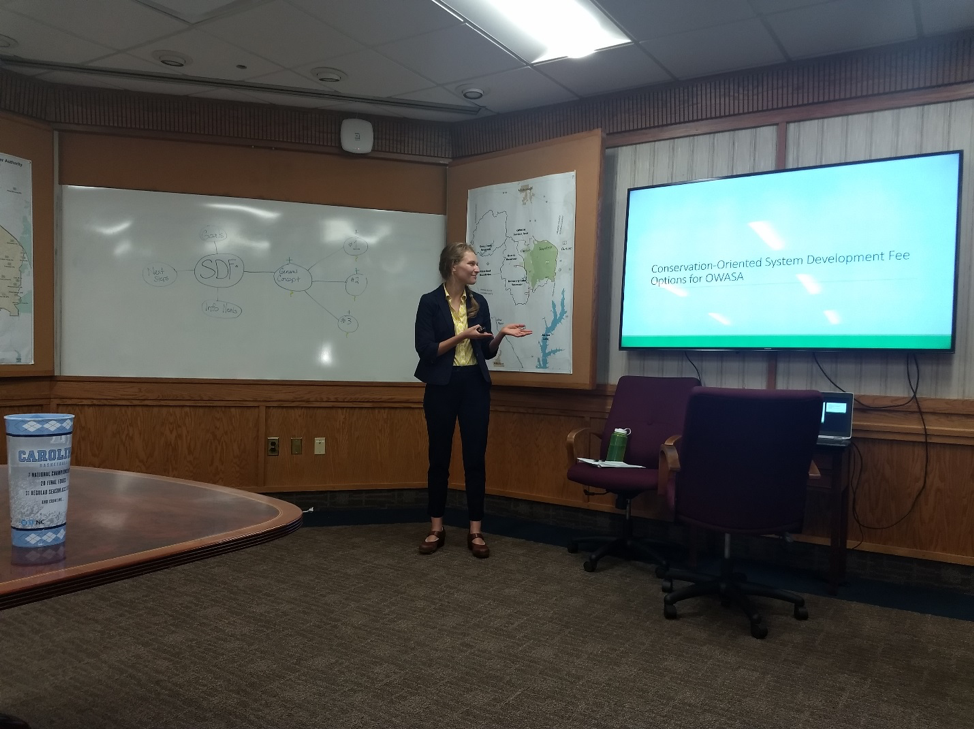

To share my research, I prepared a report summarizing my findings and outlining key considerations for designing a conservation-oriented SDF. I then presented key report points to OWASA staff and met with them to discuss the options and determine how OWASA should proceed.

Interning though the LEAF fellowship program this summer allowed me to apply knowledge gained from my classes at UNC to work on a real-world problem in my community.I found that tasks that seemed cut-and-dry when I learned them in class often required flexibility and further research in an applied setting.

By working on a fairly open-ended research question over the course of the summer, I learned how to manage a project over an extended period of time and was able to modify “the plan” as needed based on new findings.

Through my research, I saw how having access to others’ breadth of knowledge allows you to consider how sustainable measures might impact the system as a whole and to identify potential unintended consequences, good or bad. I learned the value of reaching out for different perspectives both inside and outside the organization and remaining curious about details that may not seem relevant at first glance.

This experience increased my confidence in professional settings and made me feel much more prepared to navigate the job market when I graduate. It also increased my interest in working in water and local government, which I had not previously considered. I’m grateful for the opportunity to work with OWASA through the LEAF fellowship and look forward to joining other LEAF fellows in applying what we’ve learned this summer to the Environmental Finance Center’s research projects this fall.

The Leaders in Environment and Finance (LEAF) fellowship program is supported by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Envirolink, and the NC Policy Collaboratory.

For more information about the program, please visit: https://efc.sog.unc.edu/project/leaders-environment-and-finance-leaf.