Elizabeth Kendrick is a senior Environmental Studies and Public Policy double major. She is working as an Environmental Policy Intern with the NC Policy Collaboratory during the 2020 spring semester.

Understanding the Importance of Resilience

During the Fall 2018 semester, my Outer Banks Field Site classmates and I studied how the Outer Banks, specifically regarding wastewater treatment, can be more resilient to changing weather patterns and sea-level rise.

At the beginning of the field site semester, I had a very narrow mindset of what the word resiliency actually means. I remember comparing it to the term “recovery,” believing that an individual or city is resilient if they can quickly return to their normal state following a significant change. However, throughout the semester, I quickly learned that being more resilient requires individuals to have both proactive and reactive environmental, social, and financial solutions.

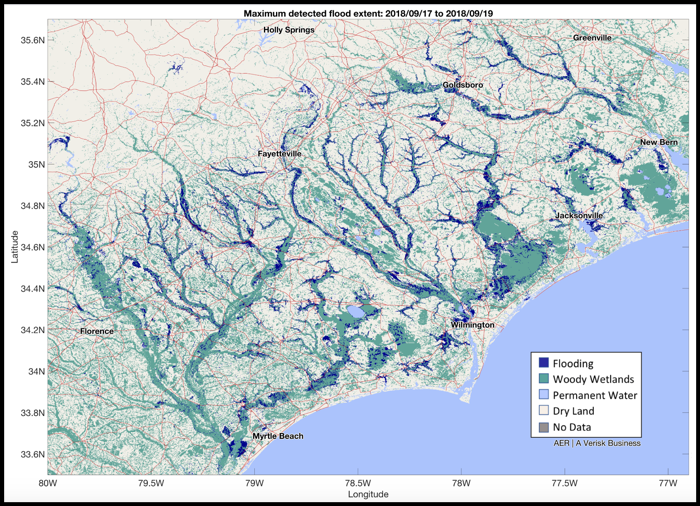

The state of North Carolina, and specifically the North Carolina General Assembly, recognizes not only the benefits but also the importance of strengthening the state’s resiliency to future storms. In response to Hurricanes Matthew, Florence, and Dorian, the General Assembly approved disaster recovery legislation (Senate bill 429, Session Law 2019-224), which included a number of response and recovery funding provisions.

One section of the legislation provided $2 million in funding and directed the North Carolina Policy Collaboratory to study flooding and resiliency against future storms in eastern North Carolina. The Collaboratory is required to deliver a final report with recommendations to the North Carolina General Assembly’s Joint Legislative Emergency Management Oversight Committee by December 1, 2020.

Studying Resilience Using a Multidisciplinary Approach

To study resiliency and ultimately make recommendations to the General Assembly, the Collaboratory is working with a wide variety of researchers who will be conducting several distinct projects that will form the whole of the study. Mike Piehler, the Director of the UNC-Chapel Hill Institute for the Environment, is managing the entire study and coordinating the work of the research team. The research team is comprised of more than a dozen faculty members with representatives from four universities: UNC Chapel Hill, NC State, Duke and North Carolina A&T.

The study includes five overarching focal areas: floodplain buyouts; infrastructure; financial risk; natural systems; and public health.

Detailing every project in the study is beyond the scope of this blog post. However, I’ve chosen to highlight a few of the specific research projects outlined below to provide examples of the type of research and activity underway in each of the five focal areas.

- Floodplain buyouts

One area of research pertains to floodplain buyouts and how floodplain buyout policies may impact the state in the future. Briefly, floodplain buyouts are the acquisition and removal of homes damaged or destroyed by flooding. While there are multiple projects studying floodplain buyouts, Todd BenDor, a faculty member with the UNC Department of City and Regional Planning, is leading work to create a model for estimating the federal, state, and local costs attributed to designing and implementing a buyout. As part of that work the team will interview emergency personnel, conduct a survey of buyout consultants, evaluate alternative approaches, and review different ways buyouts have been financed.

- Infrastructure

An example of the research being conducted related to infrastructure involves examining how flooding may disrupt the electric grid in eastern North Carolina. The faculty lead for this work is Jordan Kern from the NC State University’s Department of Forestry and Environmental Resources. More specifically, this research will evaluate the impacts of flooding on substations as well as the state’s solar power industry. From their findings, they will recommend pathways to improve grid resiliency.

- Financial Risk

Greg Characklis, who leads the UNC Center on Financial Risk in Environmental Systems, is analyzing the financial risks of flooding to communities in eastern North Carolina. Specifically, the analysis is focusing on the financial impact to communities in the Cape Fear, Neuse, and Lumberton river basins. Repeated flooding can negatively impact long-term property values making the recovery process more difficult for homeowners, while also potentially affecting the local government’s property tax base. Ultimately, after identifying who holds flood risks, including private property owners, community banks, and large financial institutions, the research will provide recommendations for managing these risks.

- Natural Systems

Another research project is studying the extent to which natural infrastructure, such as wetlands and agricultural lands, can mitigate the impacts of flooding. This work is being led by NC State Professor Barbara Doll and her colleagues at NC Sea Grant. The research will evaluate the capacity of large-scale natural infrastructure implementation projects, compare the costs and benefits of investments in natural infrastructure, and identify community needs relative to flood mitigation.

- Public Health

Finally, the fifth major area of investigation is public health. Faculty members Rachel Noble, UNC-Chapel Hill Institute for Marine Sciences, and Jill Stewart, UNC-Chapel Hill Gillings School of Global Public Health, are studying the impacts of flooding on water quality. They will use their research to establish how flooding and storm surge impact water quality and public health across multiple regions in North Carolina. As part of the research, the team will establish baseline water quality parameters and work with the state to develop tools that will allow for managers to respond and manage threats to public health stemming from future storm events.

While these five examples outlined above show a wide variety of research topics, they are not all-encompassing of the entire project. One of the interesting aspects of the study is that the research team is continually modifying and adjusting their efforts as new data becomes available. In addition, over the course of the study the research will be shaped by feedback from external partners.

Conclusively, similar to my Outer Banks experience, this resiliency project and the Collaboratory’s recommendations will allow for individuals, communities, and cities to change and expand upon their understanding of how to be more resilient moving forward.

A more detailed project brief about the study may be found at: https://collaboratory.unc.edu/files/2020/02/resiliency-project-brief.pdf