By Carsten Pran and Amanda Padden

Carsten Pran and Amanda Padden are rising juniors and Robertson Scholars studying environmental policy with an emphasis on water resource management. The Robertson Scholarship is a leadership development program that gives scholars dual-enrollment at UNC-Chapel Hill and Duke University.

With the consequences of climate change and crumbling infrastructure beginning to emerge, governments across the United States face a challenging situation in ensuring water resources for all. Not only will faulty water and wastewater systems prevent access to clean water, but changing precipitation patterns and temperatures will also reduce what water is available. Nowhere is this more apparent than in the Central Valley of California.

Water Challenges in California

Agriculture in the Central Valley is vitally important for the food supply in the United States, but acts as a major consumer of water. Beyond industrial agriculture, there are municipalities and urban settings that also require water. These interests, given their power, representation, and prominence, attain the focus of policymakers, leading to the neglect of water needs in marginalized communities, including disadvantaged unincorporated communities (DUCs) that are not connected to large community water systems.

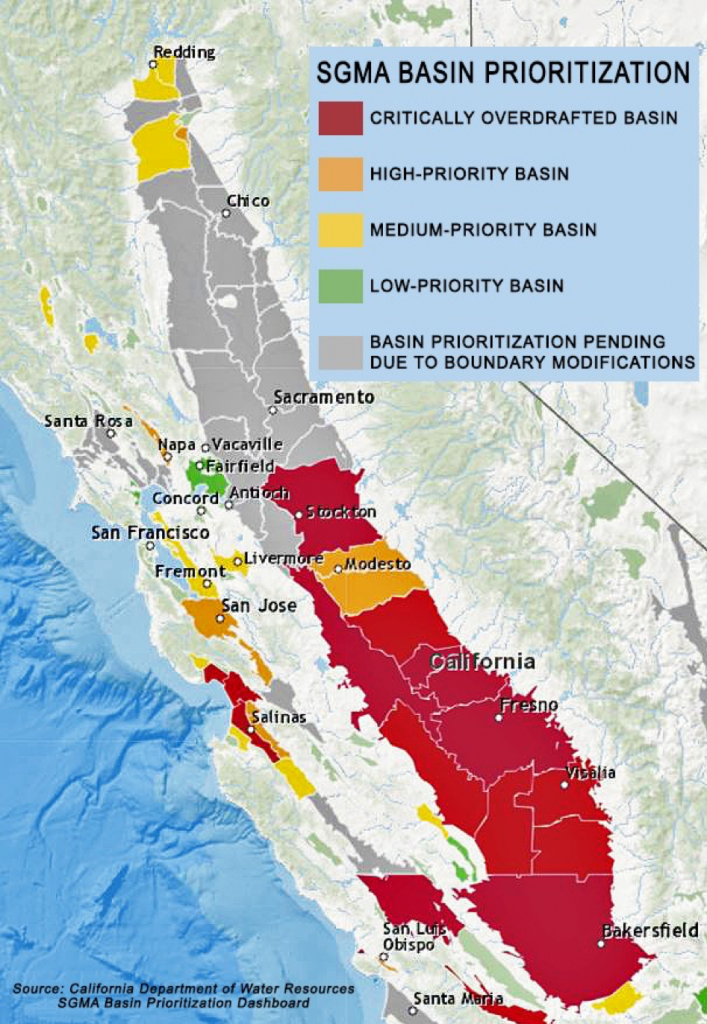

During its last major drought, California’s Central Valley had to rely on pumping large volumes of groundwater as there was very little precipitation or surface water available. Groundwater stores dropped to critically low levels, causing residential wells in some DUCs to run completely dry.

In response to this destructive megadrought, California passed a series of water bills and policies meant to bring water use to ‘sustainable’ levels. Most sweeping among them is the Sustainable Groundwater Management Act (SGMA). This bill is recognized as having implemented best practices from water management policies around the world, including a requirement for stakeholder engagement with underserved and unincorporated communities.

The Value of Stakeholder Engagement

We have interviewed several stakeholders in the Central Valley during the initial implementation of SGMA, speaking to regional policymakers, community organizers, and representatives of DUCs. From our conversations, we’ve learned that the bill largely falls short in addressing the water challenges of underserved communities.

Jasmene del Aguila, a policy advocate from the Leadership Counsel for Justice & Accountability, said “SGMA had the intent to engage and include disadvantaged communities however when you look at it as it actually played out, you don’t see that happening.”

In some stories we heard, SGMA planners only reached out to notify unincorporated communities once the plans had already been solidified. In other instances, residents of very small farmworker towns were completely overlooked as the areas they inhabit were categorized as agricultural land, rather than residential.

Though SGMA and other water bills passed in order to protect semi-arid regions like the Central Valley from agricultural collapse and dried water supplies, the people who will feel the effects of the next drought first and most severely are generally neglected.

California offers an excellent case study for the need for protecting marginalized communities in water management policies. Yet this issue of equitable access to clean water is apparent across the country, including in North Carolina.

Closer to Home: Private Drinking Water Wells in North Carolina

North Carolina is home to many unincorporated communities, due to both spatial reasons in rural landscapes and racist zoning practices through municipal underbounding.

The proportion of North Carolinians that rely on private wells and septic systems far exceeds national estimates. Lacking regulatory oversight and imposing high costs when in need of repair, private water systems pose real challenges for ensuring equitable access to clean water.

Again, we face the same questions: what does meaningful stakeholder engagement look like, and how can policies require these practices for working with marginalized communities? In California, North Carolina, and beyond, it is absolutely essential that policymakers emphasize and prioritize the needs of DUCs and other marginalized communities in a concerted and specific manner.

Without clear requirements for engagement with these communities, water management policies will only continue to enact harm on vulnerable communities.