Adithi Reddy is a junior honors student at UNC-Chapel Hill double majoring in Global Studies and Business Journalism and minoring in Sustainability Studies. Adithi spent this summer working as a Research Assistant with UNC’s Environmental Finance Center at the School of Government.

The State of Our Current Water and Wastewater Infrastructure

Imagine you are managing a small community’s water and wastewater system in rural America. The infrastructure is old and failing, causing frequent water main breaks and difficulty maintaining Clean Water Act standards of cleanliness. As the small-town utility manager, you need to keep the system from buckling under the pressure of various challenges: difficulty recruiting and retaining qualified staff, poor regulation of agricultural waste and other pollutants, and corroding pipes leaching lead and copper into the drinking supply.

While juggling the needs of customers and pressure from the advisory board to cut expenses, you run into another issue: the large costs of ensuring the utility follows regulations. The community usually pays for water infrastructure by rates charged to individual customers. However, with the community’s population shrinking over the past decade, you can no longer rely on a large base of rate-paying customers to provide a financial cushion that absorbs infrastructures costs. Instead, you will have to look for grants and loans to cover these improvements.

This summer, I interacted with multiple small water and wastewater systems plagued by the issues discussed above. Working as an Undergraduate Research Assistant at the Environmental Finance Center (EFC) operating out of the University of North Carolina- Chapel Hill, I engaged in on the ground interviews and applied research with utilities all over the country. By working with local communities through multiple pathways, I got an in-depth view of how to make a small utility work and learned about best and emerging practices in the water and wastewater sectors.

I, along with my project director Elsemarie Mullins and colleague Radhika Kattula, have been working on a series of case studies that target the viability of local government water and wastewater utilities of various sizes across the country. Clean water and a functioning sewer system are essential components of American infrastructure that safeguard the environment from pollutants, diseases, and natural disasters.

A Closer Look at the Viability of Water and Wastewater Systems

Thus, it is imperative to understand viability so that struggling systems can be improved in meaningful ways. A viable system, in simple terms, is a utility that functions as a long-term, self-sufficient enterprise that provides appropriate levels of infrastructure maintenance, operation, and reinvestment that allow the utility to provide reliable services into the future.

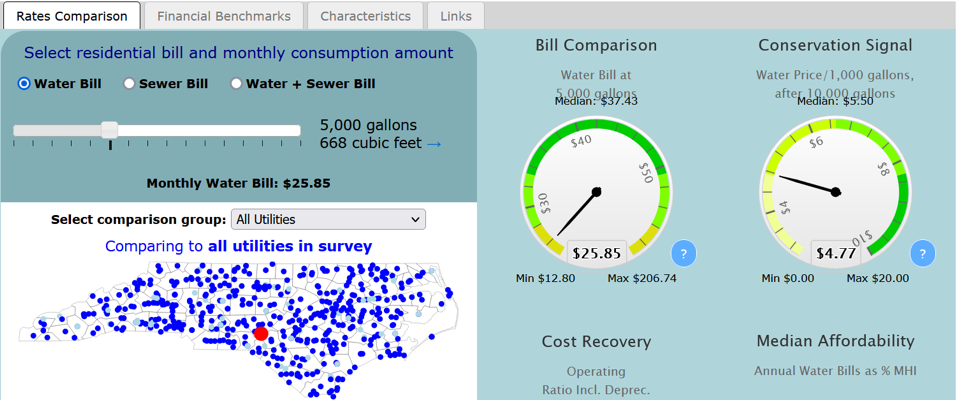

For the project, we are developing a model that assesses water and wastewater systems through a holistic framework of viability. The most effective way to learn about a utility’s viability is through conducting interviews with representatives and asking questions to determine its technical, managerial, and financial capacity.

From our interviews, we learned about several key indicators that illustrate different levels of a utility’s viability. Factors include infrastructure health and longevity, compliance with regulations, and socio-economic circumstances like median household income, as that can affect the ability of households to pay their bills on time. Finally, we distinguish between systems on a spectrum: are they experiencing complete failure, struggling, building viability, or maintaining viability?

By understanding where a utility is from a holistic standpoint, we can target solutions to their most pressing issues. This work will help state agencies provide more targeted assistance to struggling systems and equip them to ask helpful questions when deciding what assistance (including financial, managerial, and technical) to provide.

Through my work on the project, I found leveraging partnerships to be a palatable solution to increase viability for utilities. Partnerships with neighbors are flexible for various communities based on their needs, but it is often the key to long-term success. For instance, partnerships of water and wastewater systems can range from contracting out specific services (meter reading and billing), to purchasing treatment capacity, to potentially merging systems under different governance models. In aiming to increase their long-term sustainability and effectiveness, systems can consistently meet the needs and expectations of their communities and provide customers with sustainable services.

A Unique Summer Learning Experience

The EFC and the work I conducted furthered my public policy and the legal interest along with my passion for environmental management, sustainability, and environmental justice. I am interested in pursuing a career in environmental law; this experience has given me the foundational knowledge to work from the bottom-up, with communities, to find and craft solutions to real-world problems.

With the EFC, I got to learn outside the classroom setting and hear different perspectives from individuals on the ground. One of my biggest take aways from working with communities is that what the law says and what happens in practice is often quite different. Even with federal and state guidance in place, communities can choose to embark on various pathways to achieve a goal – it was fascinating to see how different theories can play out in different areas.

Learn more about the ongoing work of the UNC Environmental Finance Center here: https://efc.sog.unc.edu/