By Hallie Turner

By Hallie Turner

Hallie Turner is a junior at UNC-Chapel Hill and an Honors Environmental Sciences and Public Policy student. She spent the fall semester at the Institute for the Environment’s Highlands Field Site located on the Highlands Biological Station. Hallie is interested in working at the intersection of science and policy to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and address climate change issues.

Getting to Highlands

In the spring of my sophomore year, I sat down to register for environmental science classes. Some that caught my eye had names like “ENEC 204: Southern Appalachian Environmental and Cultural History” and “ENEC 479: Remote Sensing.” When it came time to add them to my shopping cart, I realized that the most interesting topics each came with the caveat “Taught at off-campus field station.”

This would be Highlands Biological Station, which I would soon call home for four months of my junior year. On a whim, I emailed Rada Petric, the director of the Institute for the Environment’ Highlands Field Site program, to see if I could apply for the field site after the deadline had passed. This spontaneous decision was hands-down the best one I’ve made in my time at Carolina.

Friendships and Field Trips

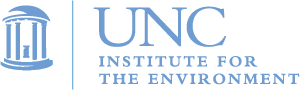

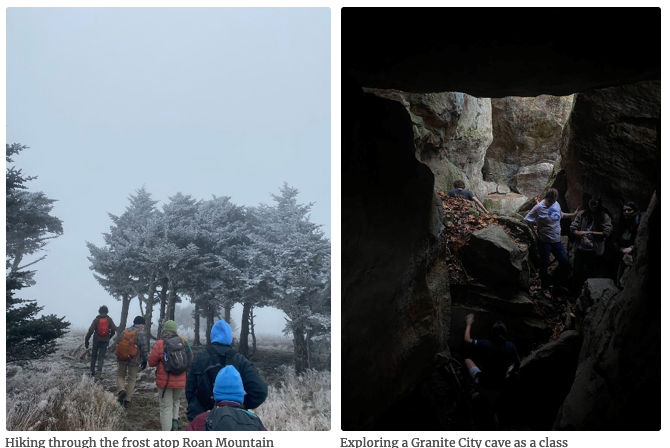

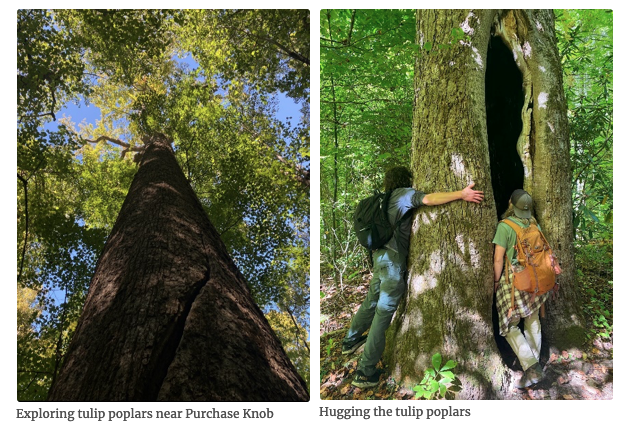

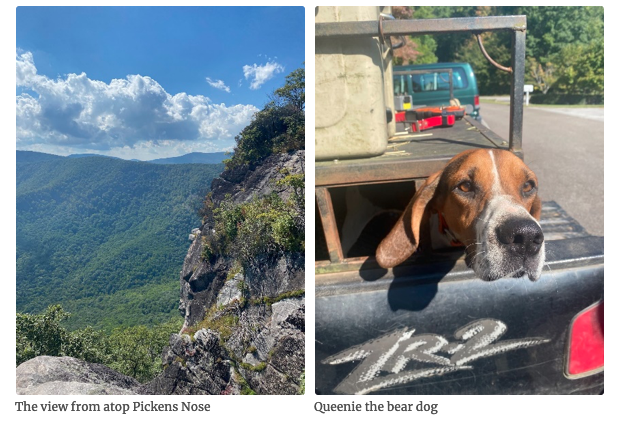

During my semester in Highlands, I’ve been immersed in 17 credit hours that consist of a group Capstone project, lectures, a seminar, a research-oriented internship, and more field trips than I can count. Here, the classroom changes to fit the environment around it: Some days it’s an acidic Anakeesta rock formation in Great Smoky Mountains National Park, other days the wild and scenic waters of the Chattooga, other days a secluded old-growth tulip poplar grove that predates the colonization of this continent.

Along the way, I’ve developed close relationships with my 14 classmates, who have become my roommates, colleagues, backpacking companions, pickleball partners, and pretty much anything else I could ask for. We ask questions that explore the relationship between land cover and microplastic concentration, the relationship between salamander genetics and mating behavior, and the costs and benefits associated with making the 40-minute trek down the mountain to Franklin for cheap groceries and CookOut.

A Unique Curriculum

I’ve always felt an affection for the North Carolina mountains from brief childhood visits. However, four months spent learning about the region’s biological and cultural diversity firsthand from local people has given me a much deeper understanding of this area than I could ever get from a vacation or a classroom in the Triangle. I came here expecting to get a few science credits out of the way, but the cultural education I’ve received through our seminar and field trips has surprisingly been just as impactful.

This research process was exhausting and frustrating, as all good research is, but it was also my favorite part of the semester and strengthened my skills as a scientist and writer more than any other experience I’ve had at UNC.

We got to explore sacred Cherokee sites at Kituwah, Nikwasi, and Kuwohi; learned about Cherokee language and cosmology from Cherokee linguist Dr. Tom Belt; and visited Western Carolina University to learn about research their archaeology department is conducting at mound sites. Hearing Cherokee perspectives on the future of park-tribe relations at the Museum of the Cherokee Indian and learning about local bear hunting practices by riding along with a bear hunter for a day were two highlights.

Valuable Research Experience

My internship project involved bushwacking to remote sites to locate near-threatened Carolina hemlock trees. My partner and I collected cores, assembled them under a microscope, sanded them, and used software to measure the ring widths. We subsequently analyzed ring widths against historical records of temperature, vapor pressure deficit, and precipitation to assess how the trees respond to changes in these variables. This research process was exhausting and frustrating, as all good research is, but it was also my favorite part of the semester and strengthened my skills as a scientist and writer more than any other experience I’ve had at UNC.

Driving down “The Gorge Road” out of Highlands for the last time will be bittersweet. I’ll leave the plateau with a newfound, interdisciplinary understanding of mountain biodiversity and the scientific method, an excess of photos in my camera roll with stories to match, and several new friendships with like-minded and passionate scientists.

I look forward to bringing these skills back to my classes in Chapel Hill, but a piece of my heart will always be in Highlands.

Read more about Hallie’s time at Highlands here: https://highlandsie21.wixsite.com/blog/post/shifting-baselines-shifting-hummingbirds

To learn more about attending the Highlands Field Site, visit: https://ie.unc.edu/education/field-sites/highlands/