By Zoe Tallmadge and Alyssa Coleman

Zoe Tallmadge is a graduating senior at UNC with a B.A. in Environmental Studies and a minor in Social and Economic Justice. Zoe has worked with the North Carolina Collaboratory for the past two years as an Environmental Policy Intern looking at water and environmental justice issues within the state.

Alyssa Coleman is a junior at UNC studying Environmental Studies with a minor in African, African American, and Diaspora Studies. This is her second year working for the North Carolina Collaboratory as an Environmental and Economic Policy Intern. Her research interests are water quality and health equity.

Defining the Issue

North Carolina has more households connected to private wells than any other state, according to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. The latest numbers from the North Carlina Department of Health and Human Services suggest that 2.4 million people in the state rely on private wells as their drinking water source. Analyses of private wells tested by the State Lab for Public Health have documented inorganic metal contamination exceeding at least one federal drinking water standard in over 26% of the wells tested. When contamination is identified, expensive treatment systems or the lack of available public waterlines remain barriers to healthy, clean drinking water.

Many residents relying on private wells are too far from public waterlines to make connections feasible and require on-site, sustainable solutions, such as treatment systems or drilling of new wells. However, 25% of the state’s private well users, reside near public waterlines.

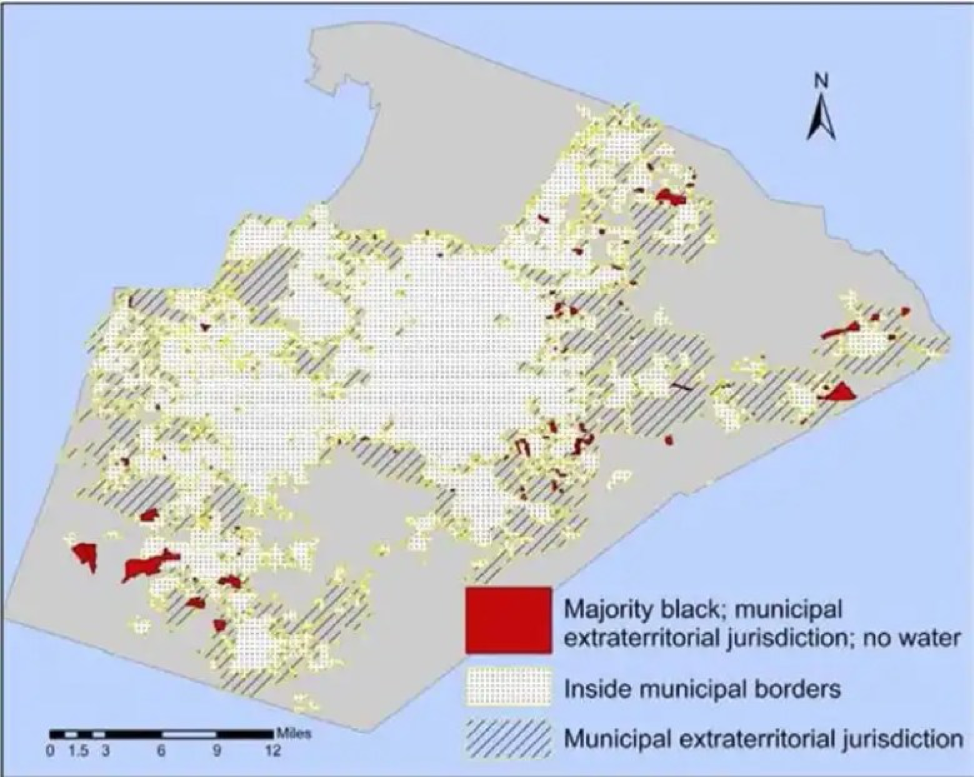

Many of these homes and neighborhoods are immediately outside municipal boundaries or, in some cases, directly surrounded by public waterlines. Those areas on a map without public water service often stand out as hole in the map and as such, are sometimes referred to as donut holes or pocket-communities.

Donut holes are a form of municipal underbounding, when communities are prevented from being annexed due to their socio-economic or racial demographics, thereby leaving households without access to public drinking water. Although these areas are not served by the local government, they may still be required to pay taxes and be under jurisdiction of the nearby municipality, creating an area of extraterritorial jurisdiction.

To tackle this issue, the North Carolina Collaboratory with funding from the North Carolina General Assembly is working to address accessibility of drinking water and ensure the wise stewardship of the large amount of water infrastructure funds coming into North Carolina.

The Collaboratory is supporting research on these topics with the UNC Institute of the Environment (IE) and the UNC Environmental Finance Center (EFC). These organizations are working to build out and enact a strategic roadmap for how to equitably invest local, state, federal, and private resources into communities experiencing contaminated wells or failing septic systems.

This group of complementary projects will answer the following questions:

- What factors influence decisions about whether to connect communities to city/county water?

- Which approaches provide infrastructure that is sustainable over time?

Working to Understand Potential Challenges

One key aspect of this research will be to evaluate and analyzed the variables that influence connection to public water supply, including information on contamination, community demographics and gaining a better understanding of the process that led to instances of successful connections.

These organizations are working to build out and enact a strategic roadmap for how to equitably invest local, state, federal and private resources into communities experiencing contaminated wells or failing septic systems.

This work is being led by the Center for Public Engagement with Science (CPES), which is located within IE. The research team has been identifying case studies and community demonstration projects as a way to understand how to provide long-term, sustainable support for NC communities that have private wells. So far, they have done this by collecting data on communities who have successfully connected to public water supplies. In addition, the CPES worked with the Orange County Water and Sewer Authority and the EFC to 1) develop a proposal to the Department of Environmental Quality for waterline extensions, 2) map existing well-reliant households for recruiting, and 3) create a community engagement plan.

Evaluating the Financial Implications

The first step in researching donut holes is to understand where they are. A team at the EFC used water meter information from Wake, Sampson, and Orange Counties to create a map of where city water is and is not served. Using GIS, the team was able to identify donut holes and commonalities between parcels in the different counties.

To research decentralized communities more broadly, the EFC has identified barriers to connecting to city water. On the household side, the EFC has found that the out-of-pocket costs for connection in Orange, Wake, and Sampson Counties are unaffordable for most families. Between land assessments, water main extension, and water meter installation, households can expect to pay upwards of $6,000 to transition away from wells—not including the new monthly water bill. On top of the costs, because of the history of exclusion from public utilities, many donut hole communities may not want to be connected because of distrust in local government. As a result, well users may rely on water filters and bottled water, which are more costly than tap water from the city.

For utilities, connection projects are complicated and expensive. To learn more about the logistics of these projects from the utility point of view, the EFC is conducting interviews with towns across the state to hear about the challenges they face and learn about well issues in their community. The EFC recently met with a member of Fuquay-Varina’s water division to discuss donut holes and expanding access to city water. The largest barriers they face are high project costs, high demand, and a lack of control over well policies—which are overseen by the county.

Identifying Solutions

Recognizing that connection is not always feasible, the EFC has investigated ways for local governments to support well users. One practice that would have a positive impact is regular, affordable well-testing. Knowing what’s in drinking water gives households more options for how to treat the water, either through well repairs and treatment or in-home filtration systems.

To learn more about how towns can carry out affordable testing, the EFC interviewed the town of Nags Head in the Outer Banks, which offers a free program for residents to have their septic system inspected. If there is a problem with the system, like groundwater contamination or flooding, the town provides low-interest loans for repairs or replacement. Even though this program is for septic systems and not drinking water, using this program as a case study is useful for towns in other areas of NC. Simple financing and community support would be beneficial for well users unsure of how to maintain their well or make repairs.

Looking Ahead

In the future, the EFC would like to use its final report as a guidebook for utilities, towns, and residents looking to dive into connection projects. The EFC will continue hearing from utilities and include their insight into the final report, ensuring that towns across the state have access to best practices for a successful connection project.

The IE will be is working with Wake County officials and other stakeholders involved in the effort to extend waterlines to well-reliant neighborhood in a “donut-hole” community in Apex, NC. Through taking a comprehensive approach to this issue the project is designed to provide long-term sustainable support for communities in North Carolina that rely on private wells for their drinking water.

For more information on the UNC Institute for the Environment visit: https://ie.unc.edu/

For more information on the Environmental Finance Center visit: https://efc.sog.unc.edu/