By Antonia Sebastian

Antonia Sebastian is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Geological Sciences and the Environment, Ecology, and Energy Program (E3P) in the UNC College of Arts & Sciences.

In 2020, NCORR released a report outlining the climate threats facing North Carolina. It is likely that we will continue to see more extreme precipitation and higher sea levels, and potentially larger and more severe hurricanes. Even without a major hurricane landfall, 2020 is shaping up to be North Carolina’s wettest year on record.

UNC’s Flood Hazards Lab seeks to understand how interactions between the built environment and climate are increasing flood hazards in urban and coastal communities, how flood risks are shifting in space and time, who holds these risks now and in the future.

Floodplains: What are they good for?

As a flood modeler, I get a lot of questions about FEMA floodplains, especially from prospective homebuyers: Am I in a floodplain? Will I flood? Should I buy flood insurance? What does this map even mean!?

I always start by pointing out that FEMA floodplains serve an important role in flood management. They provide a reasonable indication of the areas that may be inundated during a river flood or storm surge event. They also facilitate flood policy and resilience planning, like where to build a home, how high to elevate or whether to buy flood insurance.

But what many people don’t realize is that the standard FEMA floodplain maps don’t represent flooding from other sources, like street flooding driven by extreme rainfall, or the combined effects of multiple flood drivers, like the interaction between high river flows and storm surge during hurricane events. Moreover, the maps are often outdated, based on historical rainfall, river flows, and development patterns.

This doesn’t mean that they are wrong everywhere, but it may begin to explain why some communities are experiencing so much damage in areas outside of floodplains, a problem that is only getting worse because of climate change.

North Carolina Flood Resilience Project

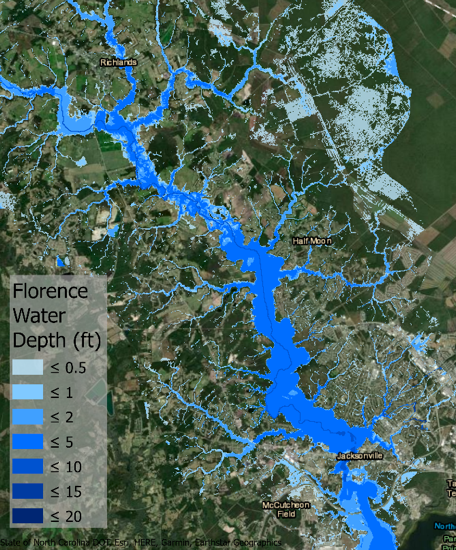

Recent Hurricanes Matthew (2016), Florence (2018) and Dorian (2019) demonstrated North Carolina’s vulnerability to severe flooding. In response, the North Carolina General Assembly approved disaster recovery legislation (Senate bill 429, Session Law 2019-224) which included funding to study flooding and resiliency in eastern North Carolina.

The UNC Flood Hazards Lab is involved in three key components of this project:

Flood Hazard Modeling

Understanding where flood hazards are and what is exposed is critical to strengthening flood resilience. We are collaborating with researchers at UNC’s Coastal Resilience Center to investigate “compound flooding” arising from multiple sources during hurricane events in Eastern NC, including extreme rainfall, high river flows, and storm surge. By linking inland and coastal models, we will investigate where these hazards interact and map their impact.

Community Flood Risks

Federal flood insurance serves as a first line of defense against homeowner losses, but the number of policy holders in North Carolina has decreased dramatically over time from an all-time high of 97,678 in 2008 to 20,152 in 2019. We are working with researchers at the Center for Financial Risk on Environmental Systems (CoFiRES) to understand who currently holds the risk and how this influences household recovery after a flood event.

Flood Mitigation

Buyouts offer one opportunity to reduce losses. Using improved flood hazards models, we are collaborating with researchers at the Odum Institute to understand the hydrologic benefits of open space protection, buyouts, and buffer zones in surrounding communities.

To learn more about this research or other research projects in the Flood Hazards Lab, visit her website, follow her on twitter, or reach out via email.