By Lucy Gray

Lucy Gray is a senior at UNC-Chapel Hill majoring in Statistics and Analytics and minoring in Public Policy and Environmental Science/Studies. She spent the summer of 2021 as an intern at the North Carolina Office of State Budget and Management, and is currently in her second semester as an Environmental Policy Intern at the NC Policy Collaboratory.

Prior to beginning my internship with the NC Policy Collaboratory in the 2021 spring semester, I did not know very much about PFAS. PFAS chemicals have a tendency to fly under the general public’s radar, but that does not mean they are not widely spread or incredibly harmful.

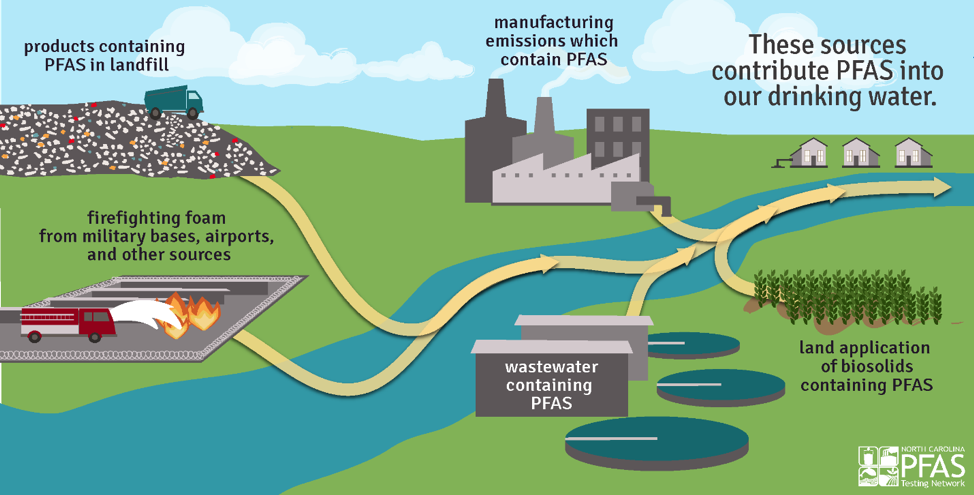

Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances, also known as PFAS are used in the manufacturing of products like Teflon and firefighting foam. These chemicals can contaminate surrounding bodies of water and air, and data about the prevalence of PFAS in the nation’s water supply and the long-term effects of the substances on human health are still relatively unknown. However, recent studies indicate PFAS can cause tumors as well as reproductive and developmental, liver and kidney, and immunological effects in lab animals. There is no current nationwide enforceable limit on PFAS in the drinking water supply.

Last spring, I spent several months with two fellow UNC undergraduate interns researching the differing approaches to PFAS regulation in the states of North Carolina and Michigan, as well as the work being done at the federal level to combat these harmful and pervasive “forever chemicals.”

NC PFAS Testing Network

In 2017, high levels of a type of PFAS known as GenX were found in the Cape Fear River watershed, a basin that provides drinking water for 1.5 million people. In response, the North Carolina General Assembly appropriated $5 million to the NC Policy Collaboratory to create the NC PFAS Testing Network (PFAST) for a 2.5-year study.

The Network is a research collaboration among university researchers, including UNC-Chapel Hill, NCSU, NCA&T, UNC-Charlotte, UNC-Wilmington, East Carolina and Duke University. Among the UNC Chapel Hill units participating in the network are the UNC Gillings School of Global Public Health, the UNC Institute for the Environment, and the UNC Department of Chemistry.

The Network is dedicated to understanding the sources, exposure levels, and impacts of PFAS. This involves analyzing water samples throughout the state, conducting studies to assess the effects of PFAS exposure on human health, and testing various PFAS removal and remediation methods. Not only does the Network benefit the broader scientific community by expanding the research on PFAS but it also helps provide information to the public about what they can do to protect themselves from PFAS in their water supply.

The NC PFAST Network published their final report in April 2021, which included a list of 60 key scientific recommendations regarding various PFAS-related topics. There were two overarching recommendations:

(1) The state should continue funding for statewide PFAS research; and

(2) Future PFAS guidance, policies, or regulations should prioritize scientific data transparency by clearly citing the data used to establish any numerical standards, limitations, thresholds, etc. and including a reference to the dataset clearly in the text of the guidance, policy, or regulation.

Although the 2.5-year study has ended, interest on this topic among lawmakers in Raleigh remains strong. Several current legislative proposals during the 2021 legislative session are intended to address PFAS issues, including additional funding for the Network for further research and projects.

PFAS Whitepaper Project

I had the opportunity to collaborate with fellow Collaboratory interns Janis Arrojado and Claire Bradley on a 25-page whitepaper comparing and analyzing approaches to PFAS regulation in North Carolina, Michigan, and at the federal level. My focus was on PFAS management at the federal level, and I found this topic to be very interesting because we were doing research and writing the paper during President Biden’s first term. Throughout his campaign, the President promised to prioritize PFAS research and regulation, and it was fascinating to follow that topic so closely in the first months of his presidency. Claire and Janis were wonderful to work with, and I enjoyed being able to discuss our research together and find ways to merge our writing and ideas.

Paper Takeaways

A major barrier to PFAS regulation is the lack of research surrounding the prevalence and long term health effects of the chemical group. Michigan and North Carolina have approached this in different ways, with Michigan taking a proactive regulation-based approach — including setting a maximum contaminant level (MCL) for PFAS in 2020 — and North Carolina prioritizing PFAS testing and research before implementing regulations.

At the federal level, PFAS legislation has a history of moving slowly. However, President Biden has made PFAS a clear priority for his administration. The President made several promises surrounding the regulation and remediation of PFAS, including to set a nationwide MCL. He also appointed Michael Regan as head of the EPA. Regan is the former head of the NC Department of Environmental Quality, and in that role he helped negotiate a consent order against Chemours when the company was found responsible for polluting the Cape Fear River watershed with PFAS. Additionally, Congress has made progress in introducing bipartisan legislation such as the PFAS Action Act of 2021 to address the threat of PFAS and hold polluters accountable.

PFAS remains an ongoing threat to our health, but the current outlook on regulation is more hopeful than it has been in past administrations. While there is no way to predict the timeline of when enforceable federal regulations will be in place, the body of research and public awareness about PFAS is continuing to grow.

For more information about this research initiative please visit: https://ncpfastnetwork.com/